The Roundtable

Welcome to the Roundtable, a forum for incisive commentary and analysis

on cases and developments in law and the legal system.

on cases and developments in law and the legal system.

|

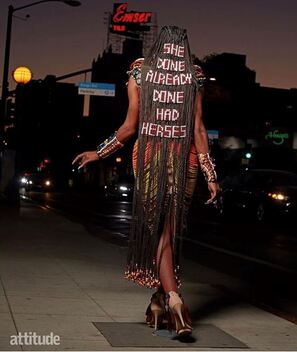

by Mina Nur Basmaci The author is a third-year undergraduate student at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she is majoring in both English and Religious Studies. She can be reached at [email protected]. The impulse to ask what a survivor of assault was wearing, or to defend police intervention based on somebody’s donning of a hoodie, implies that one’s appearance invites others to treat them in prescribed, stigmatizing ways. These explicit manifestations of respectability politics are made possible through the normalization of more implicit ones, such as those in dress codes and in grooming policies.  Indeed, the recent celebration (and commodification) of natural beauty within the mainstream cultural space—Glossier’s “no-makeup” makeup looks, messy bun tutorials, Beyonce’s “I woke up like this”—has not yet been realized in formal settings. To the extent that dress codes and grooming policies within the workplace and in the classroom continue to racialize ideas of neatness, professionalism, and appropriate versus inappropriate self-expression, the perceived decolonization of one’s regimen remains a weekend extravagance.  The Dove CROWN Research Study—CROWN standing for “Creating a Respectful and Open Workplace for Natural Hair”—found that women of color are disproportionately punished for violating workplace dress codes and grooming policies, especially in regards to hairstyle. Black hairstyles and textures are 3.4 times more likely to be perceived as unprofessional, and Black women are 1.5 times more likely to be sent home due to their hair than other women [1]. Even further, Black women with chemically straightened hair are more likely to be hired than Black women who opt for their natural hair texture [1, 2]. In 2016, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Catastrophe Management Solutions problematized the applicability of the Civil Rights Act of 1964—namely Title VII, which outlaws employment discrimination based on the immutability of race—in addressing hair discrimination as race discrimination [3]. The district court viewed hair as a mutable characteristic that may be culturally-informed and -significant, yet subject to alterations [4]. The burden hence lay on individuals to meet various hair standards. Race-based challenges against grooming policies were ultimately considered outside the scope of the Civil Rights Act. Passed by State Senator Holly Mitchell in 2019, California’s CROWN Act conflates hair discrimination with race discrimination for the first time: “In a society in which hair has historically been one of many determining factors of a person’s race, and whether they were a second class citizen, hair today remains a proxy for race” [5, 6]. The CROWN Act accordingly extends the definition of race-based discrimination in the California Fair Employment and Housing Act to be “inclusive of traits historically associated with race, including, but not limited to, hair texture and protective hairstyles.” [5] Seven other states, including New York and New Jersey, have passed similar laws, with 22 others considering following suit [7]. A federal version of the CROWN ACT was passed by the House of Representatives in September 2020 and is awaiting a Senate vote [8].  In its current iteration, the CROWN Act does not envelop private and religious schools. California’s CROWN Act applies explicitly to the workplace and the public school system. Cincinnati’s proposed version would likewise exempt religious organizations given the laws of their jurisdiction [9, 10]. Whether the CROWN Act can expand its mandate to these spheres remains an open—and contested—question, especially as at least 14 Catholic schools in New York continue to ban cornrows, braids, and other kinds of racially-indicative hairstyles in their interpretation of religious purity and modesty [11]. The relationship between the government and private and religious schools is historically inchoate. To be sure, autonomy is not new: while §168 of U.S. Code Chapter 38 protects against gender-based discrimination in educational settings, gender equality does “not apply...if the application of this subsection would not be consistent with the religious tenets” of a religious school [12]. New York’s The Dignity for All Students Act, which promises a “safe and supportive environment free from discrimination, intimidation...and bullying on school property, a school bus and/or at a school function,” likewise does not apply to religious schools [13]. A bill to change that is currently under committee review [14]. Complete self-direction does not exist either. Bob Jones University v United States (1983) successfully struck down the religious school’s ban on interracial marriage—implemented per their interpretation of the Bible—on the grounds that they would not be tax-exempt otherwise. [15]. Silva v St. Anne Catholic School (2009) also stipulates that if a religious institution is interested in receiving federal funding, they are subject to upholding the Civil Rights Act [10]. To determine a private and religious schools’ obligation to comply with the CROWN Act, then, will really be to determine their funding. The nexus between wealth, religion, and race is striking, and it will be interesting to see whether the courts will uphold, or back away from, the CROWN Act in such contexts. It will duly be interesting to see how lawyers litigate religion-based grooming challenges, especially given the racialization of certain religions and/or spiritualities—i.e. Islam, Rastafarianism, and indigenous practices —in the United States. In cases involving hijabs, beards, or uncut braids, will lawyers try invoking the CROWN Act [16]? Or will they stick to arguing the need for “reasonable accommodation” as set forth in section 701(j) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which protects solely against religious discrimination? [17, 18] Some past and present cases regarding legal intersectionalities and the CROWN Act’s potential elasticity include: I. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. United Parcel Service (2017). The UPS paid $4.9 million in settlement after refusing to hire individuals who followed religious grooming practices that conflicted with UPS’ appearance policy [19]. Further, existing employees with long hair and beards were not promoted to positions that involved customer contact. In November 2020, the UPS amended their policies to accommodate both religion and race through allowing natural hairstyles and facial hair. II. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, Inc. (2015). The EEOC filed this suit on behalf of Samantha Elauf, a Muslim woman who was set to be hired at her local Abercrombie & Fitch until they discovered she wore a hijab, which went against the store’s dress code [20]. The Supreme Court ruled in Elauf’s favor. III. Lavona Batts et al v. Immaculate Conception Catholic Academy, Jamaica (active). In 2019, Lavona Batts filed a racial discrimination lawsuit against a Catholic school in New York after the school’s principal rubbed the braids of her eight-year old son and told him they were unacceptable. The outcome of this case will set precedent for how lawyers challenge racialized grooming policies in religious settings moving forward [21, 22]. Hyperlinks [1] JOY Collective. C.R.O.W.N. Research Study. Publication. 2019. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5edc69fd622c36173f56651f/t/5edeaa2fe5ddef345e087361/1591650865168/Dove_research_brochure2020_FINAL3.pdf. [2] Guy, Jack. 2020. "Black Women With Natural Hairstyles Are Less Likely To Get Job Interviews". CNN Business. https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/12/business/black-women-hairstyles-interview-scli-intl-scn/index.html. [3] Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Catastrophe Management Solutions, No. 14-13482 (11th Cir. 2017). https://www.eeoc.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_files/eeoc/litigation/briefs/catastrophe.html. [4] Carter, Kim. 2019. "Workplace Discrimination And Eurocentric Beauty Standards". GPSOLO volume 36 no. 5, 2019. https://www.tjsl.edu/sites/default/files/black_hair_law_-_kc_article.pdf. [5] H.R. 5309, 116 Cong. (2019). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/5309/text. [6] "California Becomes First State to Ban Discrimination against Natural Hair." CBS News. July 04, 2019. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/crown-act-california-becomes-first-state-to-ban-discrimination-against-natural-hair/. [7] Padilla, Mariel. 2019. "New Jersey Is Third State To Ban Discrimination Based On Hair". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/20/us/nj-hair-discrimination.html. [8] Tannenbaum, Emily. "The Crown Act Was Just Passed By the House of Representatives." Glamour. September 22, 2020. https://www.glamour.com/story/the-crown-act-banning-hair-discrimination. [9] Sec. 914-15. – Exclusions of Cincinnati’s Code of Ordinances, Supplement 36 Update 6. https://library.municode.com/oh/cincinnati/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=MUCOCIOH. [10] Boegel, Ellen K. "Can Catholic School Hair Grooming Standards Be Discriminatory?" America: The Jesuit Review of Faith & Culture. January 16, 2020. https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2020/01/16/can-catholic-school-hair-grooming-standards-be-discriminatory. [11] Elsen-Rooney, Michael. 2019. "NYC Catholic Schools Hold Fast On Boys’ Braid Bans Despite Laws Banning Hair Discrimination". New York Daily News. https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/education/ny-hair-discrimination-catholic-school-20191202-4qqxjrvxtnd4poqa62jbnqlrme-story.html. [12] Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. A§ 1681 et. seq. https://www.justice.gov/crt/title-ix-education-amendments-1972. [13] "The Dignity for All Students Act." The Dignity for All Students Act. http://www.p12.nysed.gov/dignityact/. [14] "New York State Senate Bill S3696." New York State Senate. https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/s3696. [15] Cloud, Robert C. "Bob Jones University v. United States." Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Bob-Jones-University-v-United-States. [16] NYC Commission on Human Rights. Legal Enforcement Guidance on Race Discrimination on the Basis of Hair. February 2019. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/cchr/downloads/pdf/Hair-Guidance.pdf. [17] 29 CFR § 1605.2 - Reasonable accommodation without undue hardship as required by section 701(j) of title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2016-title29-vol4/xml/CFR-2016-title29-vol4-part1605.xml. [18] "Religious Discrimination." U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://www.eeoc.gov/religious-discrimination. [19] "UPS to Pay $4.9 Million to Settle EEOC Religious Discrimination Suit." UPS to Pay $4.9 Million to Settle EEOC Religious Discrimination Suit | U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://www.eeoc.gov/newsroom/ups-pay-49-million-settle-eeoc-religious-discrimination-suit. [20] EEOC v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, Inc., 575 U. S. 768 (2015). https://www.eeoc.gov/faces-eeoc-samantha-elauf. [21] Salvadore, Sarah. “Catholic Schools Slow to Accept Cultural Significance of Black Hair.” National Catholic Reporter, February 20, 2020. https://www.ncronline.org/news/justice/catholic-schools-slow-accept-cultural-significance-black-hair. [22] Riggio, Olivia. “Queens Mother Lavona Batts Sues Catholic School for Telling Her Son He Could Not Wear His Hair in Cornrows.” DiversityInc, November 1, 2019. https://www.diversityinc.com/queens-mother-lavona-batts-sues-catholic-school-for-telling-her-son-he-could-not-wear-his-hair-in-cornrows/. Other References Arefin, Sharmin. "Is Hair Discrimination Race Discrimination?" American Bar Association. April 17, 2020. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/business_law/publications/blt/2020/05/hair-discrimination/. Robson, Ruthann. Dressing Constitutionally: Hierarchy, Sexuality, and Democracy from Our Hairstyles to Our Shoes. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2013. Jones, Ra'Mon. "What the Hair: Employment Discrimination Against Black People Based on Hairstyles." Harvard BlackLetter Law Journal 36 (2020): 27-45. https://harvardblackletter.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/07/HBK106_crop.pdf. Images Lorna Simpson, Wigs (Portfolio), ca. 1994, waterless lithograph on felt, 182.9 x 412.8 cm., The Museum of Modern Art, New York, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/73745. Powis, Owen. "'Unprofessional Hair' and Google." Wordtracker.com. May 10, 2016. https://www.wordtracker.com/blog/search-news/unprofessional-hair-and-google. "Jaida Essence Hall on Surviving Growing up Black and Queer in a 'Terrible' Neighbourhood." Attitude.co.uk. August 12, 2020. https://attitude.co.uk/article/jaida-essence-hall-on-surviving-growing-up-black-and-queer-in-a-terrible-neighbourhood-1/23603/. Sumbi, Iman. "With the Passage of the CROWN Act, Sen. Holly Mitchell Paves the Way for Natural Hair Acceptance." Los Angeles Sentinel. July 11, 2019. https://lasentinel.net/with-the-passage-of-the-crown-act-sen-holly-mitchell-paves-the-way-for-natural-hair-acceptance.html. The opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions of the designated authors and do not reflect the opinions or views of the Penn Undergraduate Law Journal, our staff, or our clients.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|